- Modern guidelines—based on decades of global research and endorsed by respected medical bodies like the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), and National Institutes of Health (NIH):

- Total Cholesterol: below 200 mg/dL, with 150 mg/dL considered even better Readings of 240 mg/dL or higher are categorized as high.

- LDL Cholesterol (“bad” cholesterol): The goal is below 100 mg/dL for most people, and below 70 mg/dL for those considered high-risk.

- Triglycerides: Normal levels are under 150 mg/dL. Anything above 200 mg/dL is considered high (very high if over 500 mg/dL)

- Individuals with the lowest serum cholesterol or LDL-C levels carry the least risk. In other words, ‘the lower, the better’ for cholesterol levels holds.

Who Should Take Statins? (And Why It Depends)

- Statins consistently recommend as the first-line treatment, especially when paired with lifestyle changes.

- Secondary Prevention If someone has already been diagnosed with cardiovascular disease—whether it’s a heart attack, angina, stroke, or peripheral arterial disease—they should be on a high-intensity statin. Why? Because the data is clear: statins dramatically lower the risk of repeat events and death in these patients.

- Primary Prevention For those without diagnosed heart disease, statin use is based on risk factors:

- LDL ≥ 190 mg/dL: Treatment is strongly recommended This level is often genetically driven and carries a very high lifetime risk.

- Adults with diabetes (age 40–75)

- Adults (age 40–75) with LDL 70–189 mg/dL and a calculated 10-year ASCVD risk ≥7.5

Evidence Supporting Statin Guidelines

Grounded in decades of high-quality evidence from well-designed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and large meta-analyses the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration, which combined data from 26 large trials, found that for every 1 mmol/L (~39 mg/dL) reduction in LDL, there was an average 22% reduction in major vascular events, and LDL reduction2 mmol/L (77 mg/dL) reduction corresponds to an approximate 45% reduction in such events.

This finding has been confirmed by multiple meta-analyses showing that long-term statin therapy reduces the risk of death from both vascular and non-vascular causes.

Statins are also effective in individuals who have not yet been diagnosed with any vascular disease. This is referred to as primary prevention. Studies such as WOSCOPS (in men with elevated LDL levels) and JUPITER (in individuals with high inflammatory markers, like CRP, but normal LDL levels) found that statins significantly lowered the risk of first-time events⁴.

Summary Taken together, this extensive research supports a clear consensus: Maintaining lower LDL cholesterol levels is strongly associated with better long-term health outcomes. When prescribed appropriately, the benefits of statin therapy outweigh the risks in the vast majority of individuals. This makes statins a cornerstone of preventive care option, considered thoughtfully, based on evidence and individual context.

A Different Perspective: The Case for Cholesterol Skepticism

While the mainstream medical consensus strongly supports lowering LDL cholesterol and using statins when indicated, not everyone agrees. An alternative viewpoint—supported by some practitioners in functional and integrative medicine, select cardiologists and researchers, and increasingly by health influencers—challenges the dominant “lower is better” model. This perspective has sparked a growing interest in what some now call “cholesterol skepticism.”

Historical Context: How Did We Go from “Normal” 300 to “High” 200?

During the 1970s, many physicians reportedly viewed total cholesterol below 300 mg/dL as unremarkable. Critics argue that over time, cholesterol thresholds were progressively lowered, which may have expanded the number of people eligible for medication. Some suggest that this trend was influenced, in part, by pharmaceutical interests, since lower targets mean more prescriptions.

Formal definitions also evolved. For instance, the NIH’s NCEP guidelines in 1987 redefined “desirable” total cholesterol as less than 200 mg/dL—a shift from previous norms². For alternative health advocates, this suggests that cholesterol targets are a moving goalpost, not necessarily rooted in universal biology.

A Different Interpretation of the Data

Cholesterol skeptics often argue that moderately elevated cholesterol levels—particularly in older adults—may not be harmful and might even be physiologically appropriate. They point to observational studies suggesting that in some age groups, higher cholesterol levels correlate with better longevity, not worse outcomes.

One frequently cited example comes from a BMJ review of cohort studies in people over age 60. That review found no consistent association between high LDL and cardiovascular death in many older populations—and in some cases, an inverse relationship with all-cause mortality³. In simpler terms, some groups of older adults with higher LDL seemed to live longer than those with lower levels.

This idea has gained traction on social media and in books promoting natural health. The result is a popular claim that looks something like this: Claim (Alternative View): “Older people with high LDL do not die prematurely – they actually live the longest, outliving both those with untreated low LDL and those on statin treatment.”

From this perspective, cholesterol’s role as a “villain” in cardiovascular disease may be overstated, particularly in aging populations. Some proponents argue that cholesterol may play protective roles—such as supporting hormone synthesis or immune function—especially in later life or during illness.

The “Cholesterol Myth”?

A central idea promoted by this movement is what they call the “cholesterol myth”—the belief that cholesterol itself is not the main cause of vascular disease, and that inflammation, insulin resistance, or other metabolic factors may be more significant contributors.

This doesn’t mean they reject all treatments or preventive care. Instead, they often emphasize nutrition, lifestyle, metabolic health, and inflammation control over medication. They also advocate for personalized risk assessment, rather than treating cholesterol as a universal danger.

While this viewpoint remains controversial in the academic and clinical world, it resonates with many patients who are hesitant to take medication for a symptomless condition and who feel overwhelmed by the evolving nature of guidelines and public messaging.

The Benefit in Low-Risk People Is Small

One of the primary arguments is that statins offer only modest absolute benefits for people without prior cardiovascular events. Critics often cite statistics such as: “You have to treat 100 people for 5 years to prevent just one heart attack.”

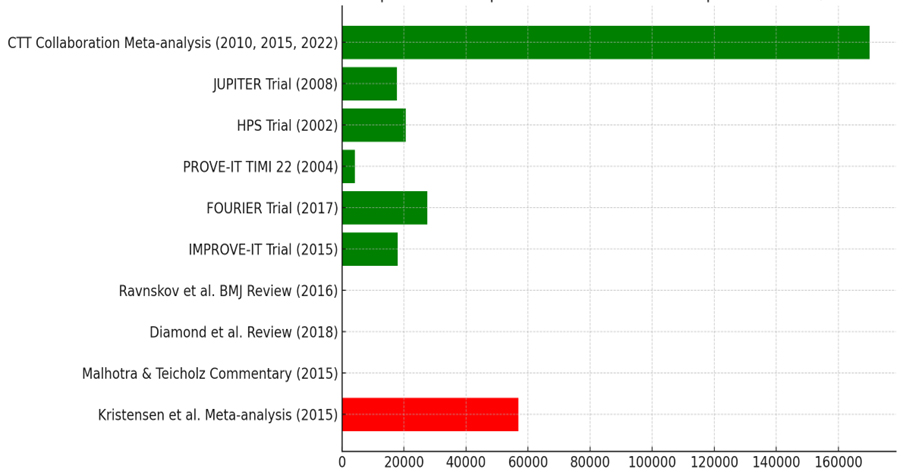

These statements are meant to illustrate the low absolute risk reduction in primary prevention. A widely referenced analysis by Kristensen et al. (2015) reviewed multiple clinical trials and found that, for many users, statins did not significantly extend lifespan.

In fact, that review calculated the median gain in survival was only a few days or weeks for most people—approximately 3 days in primary prevention and 4 days in secondary prevention¹.

This leads some patients and practitioners to ask:

“If I’m otherwise healthy, is it really worth taking a medication every day for the rest of my life for a benefit I’ll likely never feel?”

Questions about blood markers

Does LDL Even Matter?

A more controversial criticism goes further: challenging the idea that LDL is the cause of cardiovascular disease.

A 2018 review led by Uffe Ravnskov and colleagues questioned the cholesterol hypothesis entirely, suggesting that many studies show no clear link between high LDL and heart disease, and that other factors might be more important². They highlight cases where people with low LDL still suffer from cardiovascular events, and where those with high LDL remain healthy into old age. This has led to the popular notion that:

“Cholesterol is just an innocent bystander.”

Proponents of this view suggest the real drivers of disease may be inflammation, oxidative stress, or insulin resistance, not cholesterol itself. They also argue that cholesterol plays essential roles in the body, such as supporting hormone production, brain function, cell membrane integrity

This leads to concerns that aggressively lowering LDL might have unintended negative consequences, especially in aging adults.

“My grandfather had a cholesterol level of 280 and lived to 90.”

Alternative Risk Markers

Because of this broader interpretation, many practitioners outside of conventional cardiology shift focus away from LDL alone and instead emphasize other markers, such as:

- C-reactive protein (CRP) – a marker of systemic inflammation

- Triglyceride-to-HDL ratio – sometimes seen as a better predictor of metabolic risk

- Coronary artery calcium score – used to assess actual plaque burden in arteries

- These providers often recommend a more individualized and holistic approach, prioritizing overall metabolic health and inflammation control rather than aiming for specific cholesterol numbers.

Emphasis on Side Effects and Potential Risks of Statins

Emphasis on Side Effects and Potential Risks of Statins:

One of the most frequently voiced concerns from statin skeptics is the potential for side effects.

Muscle Symptoms and Fatigue:

Dr. Mark Hyman, a functional medicine practitioner, frequently cites that up to 20% of statin users report notable muscle discomfort or weakness.

Blood Sugar and Metabolic Effects:

statins can slightly increase the risk of developing type 2 diabetes, estimate a ~9–12% relative increase in diabetes incidence over time.

Cognitive and Neurological Concerns:

memory issues or cognitive changes. While the FDA has acknowledged that rare, reversible cognitive problems may occur, critics believe these cases may be underreported or not well understood. One possible mechanism that is sometimes discussed is the reduction of Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) levels.

Liver Function and Hormonal Effects

Severe liver damage from statins is very rare, and routine liver monitoring is no longer required for all patients

Critique of Pharmaceutical Influence and Medical Guidelines

Critics point out that many experts involved in writing cholesterol guidelines or conducting statin trials have received consulting fees or research funding from drug manufacturers. For example, a group of physicians in the UK published a letter in 2014 noting that 8 of 12 experts on a major NICE guideline panel had financial ties to statin-producing companies.

Expanding Definitions = Expanding Markets. Another criticism is that pharmaceutical companies benefit when cholesterol thresholds are lowered, as more people become eligible for treatment.

Concerns About Selective Publication and “Hidden” Data:

Skeptics also worry that statin trial data is largely controlled by pharmaceutical sponsors, and that: Negative or neutral results may go unpublished; Raw data on side effects may not be released for independent analysis; Published results may selectively highlight benefits over risks Validating Patient Concerns: Another critique is that mainstream medicine may not always listen to or validate patient-reported side effects. When patients express concerns like muscle pain or fatigue, they’re sometimes told, “it’s just aging” or “it’s in your head.”

This chart compares the population analyzed during the most commonly used reference publications for mainstream medicine ( green) vs the alternative point of view (red)

CDC – “About Cholesterol”, optimal levels and definitions

NCBI/Endotext – Grundy et al., “Guidelines for High Blood Cholesterol”, on benefits of lowering LDL

(22% risk reduction per 39 mg/dL) and ACC/AHA guideline highlights

Mercola J. – “Cholesterol Does Not Cause Heart Disease” (Alt perspective summary)

Mark Hyman MD – “Should I Stop My Statins?” (functional medicine view on side effects)

PharmaTimes – “NICE defends statin guidance as docs attack pharma bias” (COI and skeptic letter)

TCTMD – Collins et al. Lancet statin review (benefit-risk numbers)

Cleveland Clinic – “Cholesterol Levels & Numbers” (mainstream targets, no LDL lower limit)

ACC CardioSmart – “Natural Alternatives to Statins” (overview of supplements)

About Cholesterol | Cholesterol | CDC

https://www.cdc.gov/cholesterol/about/index.html

Cholesterol: Understanding Levels & Numbers

https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/11920-cholesterol-numbers-what-do-they-mean

Cholesterol Does Not Cause Heart Disease https://articles.mercola.com/sites/articles/archive/2022/08/09/cholesterol-myth-what-really-causes-heart-disease.aspx

Guidelines for the Management of High Blood Cholesterol – Endotext – NCBI Bookshelf https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK305897/

2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC … https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/cir.0000000000000625

acc.org https://www.acc.org/~/media/Non-Clinical/Files-PDFs-Excel-MS-Word-etc/Guidelines/2018/Guidelines-Made-Simple-Tool-2018-

Cholesterol.pdf

Review Touts Benefits of Statins, Seeks to Dispel Safety Concerns | tctmd.com https://www.tctmd.com/news/review-touts-benefits-statins-seeks-dispel-safety-concerns

Impact of renal function on the effects of LDL cholesterol … – PubMed

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27477773/

Comparing the Two Perspectives: Strengths, Weaknesses, and Clinical Implications

Scientific Rigor and Evidence-Based: Mainstream Perspective:

The conventional stance is built on a robust body of peer-reviewed clinical research and are updated regularly by expert panels who review the totality of available data.

Scientific Rigor and Evidence-Based: Alternative Perspective

View draws on observational studies and re-analyses of data. Some of its proponents are MDs or PhDs who publish thoughtful critiques—though often in lower-tier or specialty journals. This group emphasizes clinical relevance over statistical significance: a central argument is that the absolute benefit of statins is small for many individuals, and that the focus should be on personalized risk, not population averages.

Patient-Centered Care and Autonomy: Mainstream Perspective. Modern guidelines now emphasize shared decision-making, particularly for primary prevention. Clinicians are encouraged to discuss the benefits, risks, and patient values before recommending statins⁴.

Patient-Centered Care and Autonomy: Alternative and functional medicine providers tend to be highly patient-focused, often spending more time discussing lifestyle, stress, sleep, and emotional health. This approach empowers patients who want to avoid medication, take control of their health through diet and behavior changes, and feel respected in the process.

Mainstream Clinicians:

Tend to use quantitative language:

“You have a 10-year risk of 20%. A statin reduces that by 25%.”

Often refer to population-level data, which may not feel personally relevant to patients.

Alternative Clinicians:

Use more metaphors and intuitive explanations:

“Let’s cool the inflammation in your arteries by fixing your diet.”

Focus on how the patient feels, not just what the lab shows.

Risk–Benefit Analysis of Statin Use

Mainstream Medical Interpretation

For patients who meet guideline criteria, particularly those at moderate to high risk, the consensus from major organizations is clear:

Statins provide significant benefit, and the risks are small and manageable.

To illustrate, here’s what the research shows: In a group of 10,000 patients treated with statins over 5 years, studies estimate that statins may prevent:

: – 500 to 1,000 major cardiovascular events (such as heart attacks, strokes, and procedures)

– While causing approximately:

– 50 new cases of diabetes

– 5 cases of serious muscle injury¹

When framed this way, the scale tips strongly in favor of benefit, especially in those with established cardiovascular disease or a high baseline risk.

It’s also worth noting that: Most side effects are reversible. If a patient develops muscle pain or elevated liver enzymes, the symptoms usually resolve after stopping or switching the medication.

In contrast, cardiovascular damage—such as a stroke or heart attack—can result in permanent disability or death, making the consequences of untreated high risk potentially far more serious than the common side effects of therapy².

Long-Term Safety-Risk of Side Effects: Context and Management

Concerns have also been raised about whether statins may have long-term negative effects outside of the cardiovascular system (e.g., cancer risk, memory loss, or non-cardiac mortality). To date:

Large meta-analyses have shown no increase in deaths from non-cardiac causes, such as cancer³.

In fact, in high-risk groups, statins are associated with a reduction in overall (all-cause) mortality—not just fewer cardiac events.

This means that patients who are likely to benefit from statins may not only avoid a heart attack, but may live longer overall, without evidence of increased risk in other health domains.

While the mainstream medical community emphasizes population-level benefits of statins, the alternative view focuses more on individual-level tradeoffs, particularly in people with low to moderate risk. This perspective doesn’t deny that statins reduce LDL and cardiovascular events—it questions whether the magnitude of that benefit justifies lifelong medication, especially for those who feel well and have no prior history of vascular disease.

Focus on Absolute Risk Reduction

A key argument is the difference between relative and absolute risk. For example: If someone has a 10-year cardiovascular risk of 10%, and statins reduce that risk to ~7%,

the absolute risk reduction is only 3%. That means 97 out of 100 people would not have had an event either way.

This leads to the commonly heard challenge: “Why expose 100 people to side effects to help 3 avoid an event?”

This framing emphasizes the Number Needed to Treat (NNT)—how many people must take the drug for one person to benefit—and contrasts it with the Number Needed to Harm (NNH), which may be closer than commonly acknowledged if side effects are underreported or underestimated.

Quality of Life and Day-to-Day Impact

The alternative view also centers on quality of life. If even 5–10% of statin users experience muscle pain, fatigue, or cognitive effects, that’s potentially more people affected negatively than those helped in low-risk groups.

As one skeptic summarized:

“Statins slightly tilt the long-term odds—but at what cost to how I feel today?”

This concern becomes even more pressing in people who are active, sensitive to medications, or managing multiple health priorities.

Long-Term Uncertainty

Another issue raised is the lack of long-term data over several decades. Most statin trials last 3–5 years. Skeptics ask:

What happens after 30 years of continuous statin use?

Could there be subtle cognitive or metabolic effects that only emerge with extended exposure?

Are we fully aware of what prolonged inhibition of cholesterol synthesis does to hormonal, neurological, or immune function?

Mainstream experts counter that we now have real-world experience with millions of patients on statins for 20+ years, and no major late-emerging risks have been observed. In fact, these patients often live longer. Still, the desire for caution remains a core value in the alternative camp.

Integrative Synthesis: The Best of Both Worlds

While mainstream and alternative perspectives diverge in strategy and interpretation, they ultimately share a common goal: preventing cardiovascular disease and optimizing patient health. A thoughtful synthesis that blends the scientific rigor of conventional guidelines with the individualized, lifestyle-focused ethos of functional medicine may offer the most balanced and patient-resonant care.

Statins are a powerful, evidence-based tool—but they are not a panacea, nor the only tool. Lifestyle remains the cornerstone of cardiovascular prevention, and patients’ beliefs, values, and preferences must be honored.

The effort to self-educate is essential. However, it is also crucial to understand the quality and scientific value of the information source.

Use online calculators or even coronary artery calcium (CAC) scans to see your actual risk, not a generic one. If someone’s CAC is zero, they may reasonably delay statins. If it’s high, the risk becomes more tangible—and so does the need for medication.

Make Lifestyle the Common Ground

Taking a statin is not a substitute for a healthy lifestyle—it’s an extra layer of protection.

Collaborate on diet and physical activity goals.

Monitor Closely and Follow Up Early. If you agree to try a statin, schedule a follow-up in 6–8 weeks. Discuss side effects openly.